For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than a screen, I have converted this entry into an easily printable pdf file:

In life, a person can take one of two attitudes: to build or to plant. The builders might take years over their tasks, but one day, they finish what they’re doing. Then they find that they’re hemmed in by their own walls. Life loses its meaning when the building stops.

Then there are those who plant. They endure storms and all the vicissitudes of the seasons, and they rarely rest. But unlike a building, a garden never stops growing. And while it requires the gardener’s constant attention, it also allows life for the gardener to be a grand adventure.

Gardeners always recognise each other, because they know that in the history of each plant lies the growth of the whole world.

- Paulo Coelho, Brida

I don’t normally begin essays with a quote, and certainly not as long as this one. But I want to write about gardens as a spiritual metaphor, and this insight from Coelho springboards us to where I want to begin.

I can safely assume that you grasp the key differences between spiritual builders and gardeners — the vibrancy and living-sacrifice involved in gardening, the generosity, the openness, finding your place in the continuum of history and nature, a respect for creation, a sense of custodianship instead of ownership.

To garden is to enter into a lengthy, frustrating, passionate love affair with creation. It breaks the barrier between the individual body and the world: the meeting of your knuckles and soil, loam crusting beneath your nails, smell of wet dirt in your nostrils, taste of chlorophyll on your tongue. A plant is a vulnerable, tempestuous lifeform, almost alien to us with its rhythms and seasons. And yet we need flora to eat and breathe and survive on this planet. Don’t forget, we first had our being in a garden.

Being a life-gardener in the way Coelho describes must be more than cultivating snootiness toward builders; no matter how tempting it is to sneer at their foolish, self-entrapping walls. There are risks inherent in gardening too — growing the wrong types of plants, neglecting some to focus on others. And most concerning: what if our garden is full of weeds?

Among the many good songs from the Avett Brothers’ decades-spanning oeuvre is a tune I often return to. ‘Ill With Want’ features the best kind of lyricism — deeply personal to the singer but universally applicable, and although it may be dark, it’s honestly so.

It begins:

I am sick with wanting

And it’s evil and it’s daunting

How I let everything I cherish lay to waste

I am lost in greed, this time it’s definitely me

I point fingers but there’s no one there to blame

You can listen to the whole song here (even better, listen to the entire album, ‘I and Love and You’ which is filled with simple longs of love and heartbreak and truth).

In our world of unbridled striving and yearning and desire, we are blind to our greed. In our gardens, we move from patch to patch, planter to planter, pruning and watering the vegetation in various seasons. Some plants we pluck out, roots dangling like torn nerve endings, and we replace them with something more aesthetically pleasing. In this way we think we are dealing with our desires by merely substituting them for another: instead of possessions we chase experiences or relationships; instead of fast fashion it’s vintage thrifted; no more grindset, now we do slow living; analogue for digital. We swap maximalism for minimalism, but we never stop wanting. We only address the symptoms, never the disease.

There is something wrong in our gardens, we all know it. Nothing is growing quite as it should, some plants just won’t take, certain flowers we once loved have withered on the stem. If only we had a bird’s eye view of this garden of ours, then we would see the problem isn’t which vegetables or flowers or shrubs we’ve planted or where, but the spreading weeds which grow silently among everything else, choking the life. Our garden is poisoned by greed.

There are some weeds which are worse than others; pretty-looking species like ragwort, lupin, red clover, and certain species of fern, can poison the groundwater, rendering it undrinkable for humans or toxic for other plants. Other weeds have roots which alter the pH level of the surrounding soil, leaving it inhospitable for competing species. Greed is like this, it kills as it grows. It only leaves room for more greed.

There’s a difference between wants and needs, no matter how we try to convince ourselves otherwise. And most of us have our basic material needs met, or could have them fulfilled with minimal effort. But there is one great need which lays unfulfilled at the centre of our souls, which, as Carl Jung put it, is the key truth behind every addiction, every manic desire, and that bottomless pit of yearning. We all seek to connect with the Divine, to commune with God. Another way to put it is that our gardens are incomplete without the Tree of Life.

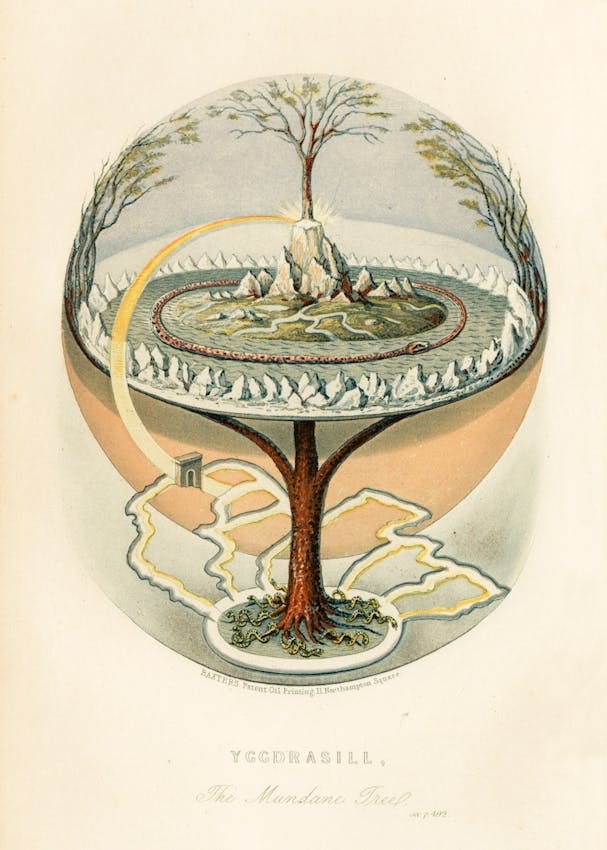

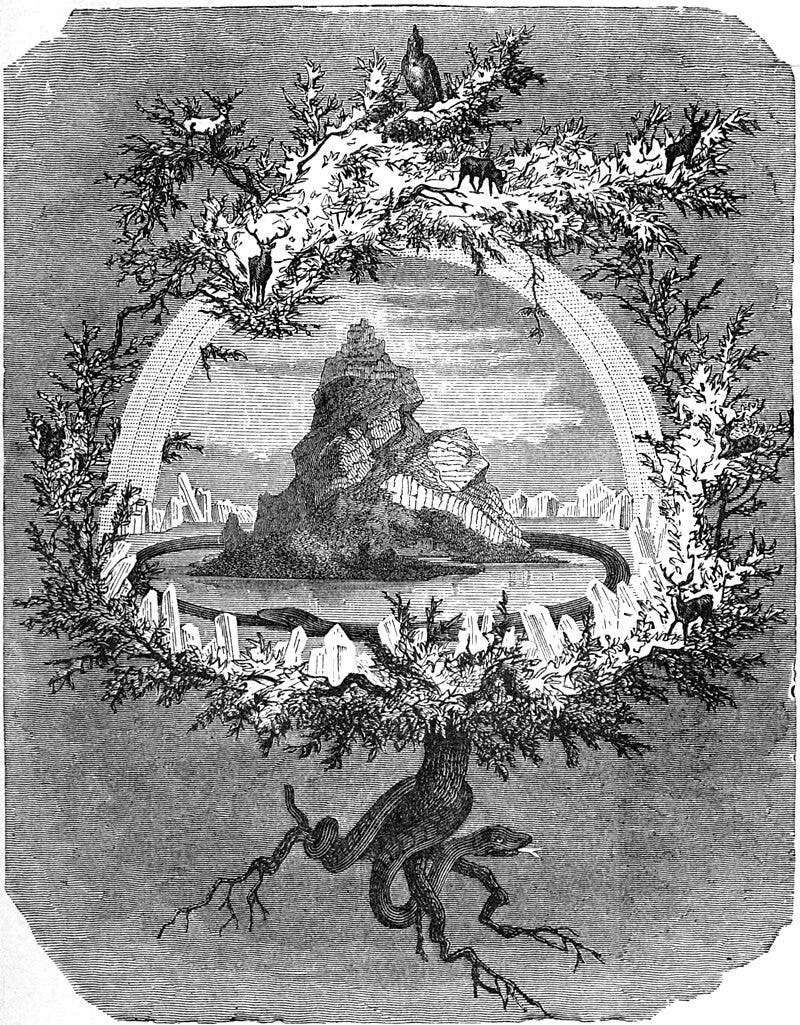

When I think of the Tree of Life, I picture Yggdrasil, the world-tree of Norse cosmology. I witness a divine seed planted on this fallen earth, in this rough and scrabbly soil, by the great Gardener himself. I see a sapling whose limbs are filled with the pressing desire to grow and expand infinitely and fill your entire life. Its tap root draws water up from the hidden aquifers of spirit and soul, nourishing your entire being, leading to unimaginable flourishing. This glorious Tree belongs at the centre of your garden.

Every plant we cultivate — all the people, places, experiences, and things we love in our lives — may in themselves be good and beautiful. But we will never truly be satisfied, our garden will never truly flourish, while the weeds grow long and thorny. And the Tree cannot flourish among the poison of the weeds. It will remain stunted, fighting for space among the knotted vines, tortured by the toxicity of the soil, choking on the bitter groundwater.

Our problem is that we do not cultivate the soil of our souls to receive and nourish the Tree of Life, instead we distract ourselves by playing around the periphery of our lives; mincing about the placement of certain hedges, discussing whether the bougainvillea will suit the trellises we constructed near the rotunda. Does the palette of the rose bushes match the aesthetics of the frangipani? And as we waste our time, the weeds are growing, choking, killing. The soil at the core of our lives is lying barren. As the Avett Brothers say, we are possessed by our greed, slave to it.

One of the main problems, I think, is our entitlement. We have a right to the things we want, because it's our garden. Our life. Aren't we free to exercise our own will? But the Avett Brothers have a different view on this sensible-sounding idea:

Free is not your right to choose

It's answering what's asked of you

To give the love you find until it's gone

Freedom is not found by getting what we think we want. Any grown person knows this; we've all chased greener pastures only to sense the nagging dissatisfaction of getting exactly what we wanted, becoming disillusioned, then reframing our desires to focus on something else, beginning the cycle again. An endless treadmill of desire and disappointment.

The Avett Brothers say freedom is found in mutual obligations of love, not by pursuing self-satisfaction. The strange irony is that we only discover true freedom via self-sacrifice. The only antidote to the pervasive poison of greed is to care more about others than ourselves. This is not a Buddhist approach of 'killing your desire' until you're a passionless vacuum, a rock garden devoid of life. Instead, it's recognising that there is a base need which is going unfulfilled, the aquifer beneath our garden isn't being properly channeled. Right now this life force is being swallowed up by the deadly weeds, which continue to spread their toxins throughout our flower beds. But if this water was instead nourishing the Tree of Life, rivers of living water could spring forth from its roots, a fountain to irrigate the depth and breadth of our souls.

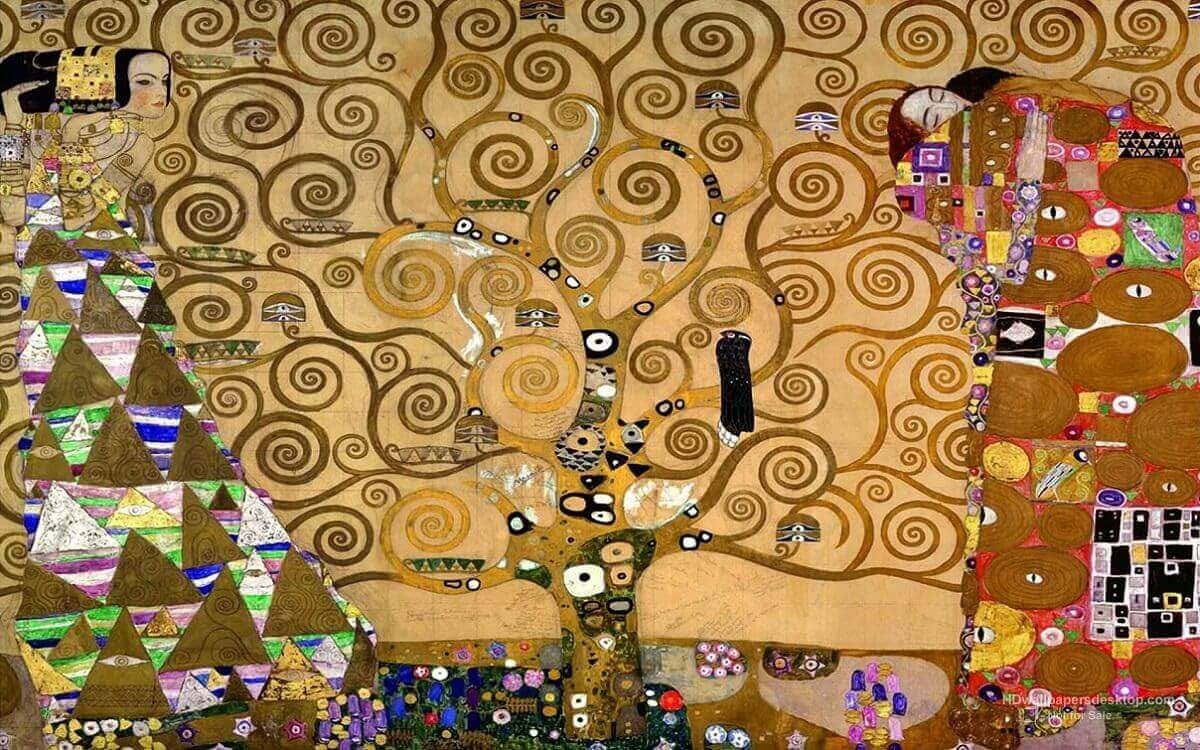

Imagine if you tore out the weeds and allowed the Tree to mature. Your garden would be transformed. It would remain yours, but more alive than ever before. Every plant bursting into freshness, every bud blooming and leaf unfurling, the contrast between light and dark made clear. You can finally see with clarity which flowers are thriving and which are wilting, rotting. Which shrubs are planted in the wrong place, receiving too much sun or too much shade. And with the Tree of Life shining in the centre of it all, the remaining weeds are so obvious. You pluck them with relish. There's no need for greed here, you know the damage it can cause to the rest of the garden. And no weed, no matter how deep-rooted or wide-spreading, could compare to the splendour of the Tree.

The Tree of Life is a cosmic growth, its tendrils stretching forwards and backwards in time, its roots spreading throughout your entire history, sub-planting everything, healing and redeeming every inch of scorched earth.

As the Avett Brothers sing in closing:

I need for something

Now let me break it down again

I need for something

But not more medicine

Our endless outbursts of greed are misshapen versions of our one true need. The world will continually sell us the next medicine (which won’t ever fully work), but the Tree of Life comes as a gift. Will we leave it to languish beneath a mess of strangling, rotting vines?

Let us clear away the weeds, give the Tree our full attention, and be amazed by how the gardens of our soul begin to flourish with it at the centre.

Love it, my friend.

I am in the process of reading an excerpt from an essay by Charlotte Mason titled “Concerning Children as Persons”. She writes on “Some Forms of Liberty”, asserting, as you do, that true liberty is to be set free from one’s own desires, and to do that which is our duty. She points out that so many adults themselves live their lives by what they elect and choose to do because they think they have “kindly instincts and benevolent emotions”… This delusion strikes me as being sneaky in our hearts like a weed, growing up unnoticed. Her whole essay is relevant to your piece here, and I appreciate them both! Mason emphasizes much of this comes from self-consciousness (emphasis on self, selfish), and I love the image you’ve given of making the center of our attention the Tree of Life rather than ourself.