For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, I have converted this entry into an easily printable pdf file:

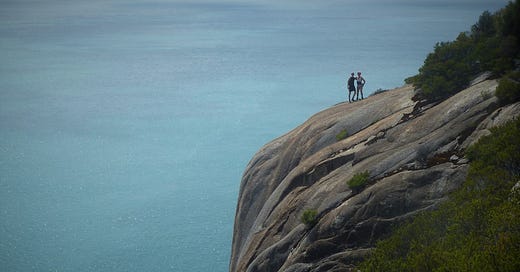

Day three of your hiking trip. Your neck and legs are sore and you can’t look at your backpack without a mixture of fondness and revulsion, like it’s a photograph from when you were 19 and grew your hair way too long and wore t-shirts for bands you weren’t cool enough to listen to. You appreciate how much your pack can hold — tent, sleeping bag, food, portable stove, clothes. But you hate how it feels to strap it on, how it weighs you down with each step until you feel like a dumb mule, snorting and staring numbly ahead after each heavy footfall. Later in the day, you glare at your friends plaintively, wishing they would slow down or at least take longer rest breaks. But they beckon you up the trail’s curve with joyful voices.

“The coast is just around the corner! And look, the beach is empty!”

You find the last reserves of willpower somewhere in your thighs and push yourself over the crest of the hill. And then you see it, the shining blue of the ocean shoving itself up against white sand and gnarled trees. It’s a deserted pirate cove, a bay at the world’s end, and it’s been laid out for your enjoyment. All you had to do was put one foot in front of the other, and you were transported to the edge of the map.

Many people love the idea of experiencing something like this, but miss out on the most crucial element. They mistake enjoying an escape into the natural world for separating themselves from all of society, even the society of loved ones. But I don’t think much of existence is worth experiencing without friends to experience it with.

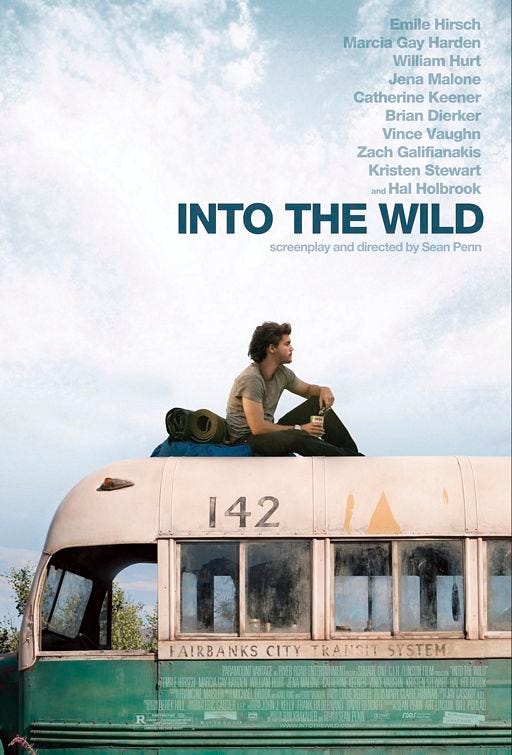

One of my favourite waymarkers or touchstones is the 2007 biographical film Into the Wild, based on the true story of Chris McCandless as documented by Jon Krakauer in his 1996 book of the same title. The film is more like a novel than a standard biopic, and it’s one of those rare instances of a movie outshining the book. Add in the original soundtrack by Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam, and humanity appears to have reached the difficult to rival book-film-album trifecta. Each is a high quality piece of art on its own merits, and yet when experienced in tandem with each other, the sum is somehow more than its parts — a trinity of adventure, philosophy, and wilderness which leads the audience to harsh but necessary lessons.

I call Into the Wild a touchstone because it’s one of those waymarkers you can pass by multiple times on this spiritual journey and each time it’s pointing you in a different direction. On the second or third time around, you’ve aged (and hopefully matured) and you’re able to appreciate something new about the tragic story. Into the Wild isn’t the simple wanderlust propellant that it appears at first blush, but a complex and cautionary tale about youthful arrogance and individualism taken to extremes.

I was 17 when I first watched the film, studying it as a text in a highschool English class with a particularly cool teacher. As a protagonist, Chris is brimming with the kind of uncompromising idealism that lit my spirit aflame. Chris graduates university, drains his bank accounts so he can donate it all to charity, ditches his family and his car, and sets off backpacking across the U.S.A. — leather-tramping along the byways of 1990s America. He’s intelligent, thoughtful, drawn to nature, and in pursuit of ultimate truth. He quickly develops a clear goal: to venture into the untouched purity of the Alaskan wilderness.

Chris also encounters an array of kind and loving adults; people who want to look after him in various ways, people you’d think he could build relationships with. But Chris is too intent on his individualistic goal: to abandon civilisation and live in isolation in the Alaskan wilds. To return to the innocence of Eden. He’s driven by the desire to escape the ills of modern life — insatiable consumerism, his parents’ broken marriage and noxious behaviour, the apathy of chasing dollars and reputation, the general dearth of spirituality in a material culture. He’s so focused on escaping into natural beauty that he’s blind to one of the most beautiful things any of us can experience: to be cared for and loved by another person.

There’s Wayne, the tractor driver who takes Chris in and gives him a job and a community; there’s Jan and Rainey, two ageing hippies driving around the country in a campervan who try to look after Chris; and most heart-breakingly there’s Ron, a veteran who tragically lost his own family and who loves Chris so much he offers to adopt him. Chris characteristically evades Ron’s vulnerability and slips away, off to Alaska, the wild, and the inevitable tragedy.

I think it was at this point in the film that I recognised a key difference between me and Chris, even though I had otherwise admired his courage and purity in leaving the world behind to seek a higher truth in untouched wilderness. Before I knew how Chris’ story ended, I knew that something was wrong when he callously rejected Ron’s offer of a father-son relationship — it was a sour note clanging in the symphony of Chris’ noble pursuit. You can say he was broken, traumatised by his own deceptive father and dysfunctional family, but here was a caring and loving man extending the warm hand of friendship and fathership, and Chris was too blinded by his vision to see it. Which takes us to the gut-punch of the ending of his story.

*spoilers ahead*

Chris ends up dying in Alaska, stuck out alone in the middle of nowhere, after many weeks of living his idealised vision. He’s killed by his own arrogance; first he runs out of food and then ingests poisonous berries. But more than just a sad story about a foolhardy young man, the cruel irony is what was found in Chris’ diary when his body was uncovered by passing hikers. Not long before he passed away, he came to the realisation that an isolated existence limited any enjoyment he might be experiencing. “Happiness is only real when shared,” was Chris’ brief observation. And it’s probably his greatest insight. He was certainly more qualified to weigh in on the subject of solitude than most people, after years of tramping and flitting from friendship to friendship, followed by months spent isolated in the Alaskan wilderness. He realised too late that what Wayne and Jan and Rainey and especially Ron had been offering was another person to experience life with, and without that, what kind of happiness can there be?

A young man seeks fulfilment by leaving civilisation, only to realise that civilisation has one redeeming quality — it has other people to share our wonder, our joy, our curiosity, our sorrow, our pain. To reduce life down to only me and impersonal nature is to risk reducing myself to a mere beast. Maybe if Chris had found a faith out in the wilds he wouldn’t have felt quite so alone, but I also think most faiths would have led him to his final realisation sooner, before it was too late.

Now when I dwell on Into the Wild I’m thankful for it in several ways. It points in the direction of adventure, it encourages me to take risks and abandon comfort to seek something more. But it’s also a cautionary nature, foregrounding the many individuals who could have been friends or even family to Chris, if he’d let them be. For where I’m at now, the story is more warning sign than waymarker. Whenever I’m drawn toward the path of individualism, of avoiding vulnerability, of preferring solitude over relationship, I remember Chris and remember his final words: “Happiness is only real when shared.”

And I think this principle should be vitally applied to our spiritual journeys. We need to recognise the danger of ‘going at it alone’. Because although it’s true that we are each a unique creation, with individual selves and minds and souls; and although it’s true that each of us is singularly responsible for what we do with the gift of life, individualistic soul-searching tends toward isolation. The last thing we need in our present age is more loneliness, more time to ourselves, more navel-gazing. We need to learn how to love and be loved. We need to learn how to walk this trail with others.

Personally, I’ve never been on a hike or in the middle of a camping trip and said to myself, “Gosh, I sure wish there was nobody here to enjoy this with and I only had my own thoughts for company.” So when I read or watch accounts of the rugged individual setting out to hike or travel or explore with nobody for company, with a seeming revulsion for humankind, I feel a distance and a pity for them. And the same goes for people withdrawing from the world or relationships to seek some higher ‘spiritual truth’.

Because what kind of happiness is there if you aren’t sharing it with someone else?

I read the book when I was a teenager, and it had a profound affect on me. I remember kind of gushing about it to a friend's dad, who looked at me with a puzzled expression and asked 'why would you admire a guy who went into the wilderness and died?'. I remember deciding not to try to explain it any further. I was surprised that this hippie-era guy didn't understand. The dying wasn't the point, obviously. Chris had a yearning that conventional contemporary society couldn't satisfy. Don't we all have that?

Ugh, this movie is one of my top five favorite movies of all time. I watched it for the first time, maybe in early high school, and cried and felt irrevocably changed. Then I bought it on DVD so I could watch it again. It would take a few years before I would grab and read the book. Which also made me cry and feel changed in a way. As someone who struggled with their own mental health, I felt like I could understand part of McCandless' struggles. He felt like he didn't belong in the life he was placed in and needed to leave and go explore. Then he found Ron and while to us it was a chance of love and redemption, he wasn't ready for it. He didn't think he was worthy of that kind of love, even though to us that seemed silly. So he turned it down to continue his journey. When he was out in the wilderness and he realized that he was alone and that he messed up, it was then he understood that he was only really happy when he could share in that happiness with others; not when he was by himself in the bus. It is such a sad and heartbreaking story and I love it all the same. What a lovely piece you've written.