This short story ended up not being so short, so I’ll be releasing it in three parts. This is Part 2, you can read Part 1 here:

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, I have converted this entry into an easily printable pdf file:

The peak of the mountain was cleft in two and smoke billowed from the gap in the rock like the mountain was on fire. Niccólo stood on the threshold of the cave, the shrine of the Oracle, and his body was buffeted by the winds. He had been searching for this place for months and had faced countless trials to get here. But still, he hesitated. The smoke was dark and pungent, perfumed with incense, and Niccólo peered into the chasm. Cutting through the high note of the fluttering wind came a different, deeper sound. A voice was calling him from within the darkness and he shivered. The voice was familiar.

Niccólo and the donkey left Byzantium and after three months of walking they had travelled beyond the certainty of maps — at least, any maps that Niccólo had ever seen. As weeks bled into each other, Niccólo became used to the rhythm of being guided by an ass. Each morning, he would load up the donkey and it would snort and stamp and twitch its ears as if listening for a whistle or a call, and then it would trudge off, its nose down and head bobbing, drawn toward some ultimate destination like it was being pulled by an invisible thread. The ass had not spoken since that first day in Byzantium, but Niccólo began wishing that it would. Niccólo talked to the beast regularly and the occasional reply would have been welcome.

Their route skirted the edge of the Holy Land and led them into high, chalky mountains, zig-zagging between spotty villages where locals smiled and spoke a little Greek and gave Niccólo food and refused any payment. On the other side of the range stretched grassy plains. Even from the high vantage, Niccólo could make out no end to their expanse. When the sun set behind the mountains and the light was purple, the undulating grasses looked like an endless ocean, stretching toward a darkening horizon.

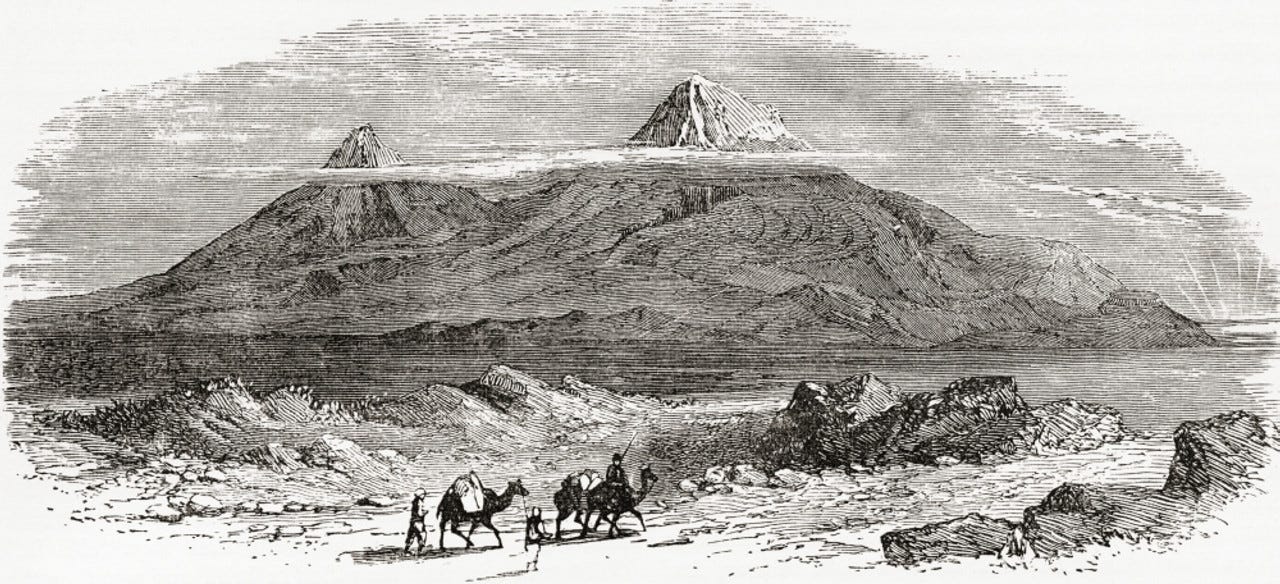

Weeks later, when Niccólo and the donkey arrived at the inland sea known as the Qazim, he wasn’t wearing a scrap of clothing and the only thing he carried was a painfully empty stomach. He was half-insane from the hunger and from the infinity of the plains. The sky was too big out there, the grassy fields too uniform and endless. And he had been robbed by three separate groups of brigands; bored mercenaries with sleek horses, round shields, and thin moustaches, all swearing fealty to some distant lord they referred to as ‘the Qahn’. The first group took his money and other valuables at swordpoint, the second group took the victuals he had stored up from his time in the mountains, and the third group demanded the donkey. But when Niccólo refused to part from the beast, even with a dagger flashed in front of his face, the soldiers laughed and demanded his clothes instead. They were made from expensive materials, and besides, the donkey was decrepit and would slow them down.

That had been five days ago, and Niccólo barely recognised the garbled reflection he saw as he knelt in the brackish waters of the Qazim. He was thinner than he’d been since he was a boy. His beard had grown fuller, but was more grey than he’d known it, and his skin had been burnt into a fleshy pink.

After hours of lying in the cool relief of the waters and drinking from a freshwater stream he found trickling nearby, the donkey brayed and Niccólo wondered if he really had gone mad out on the plains. Because walking toward him on the shoreline were two people without heads.

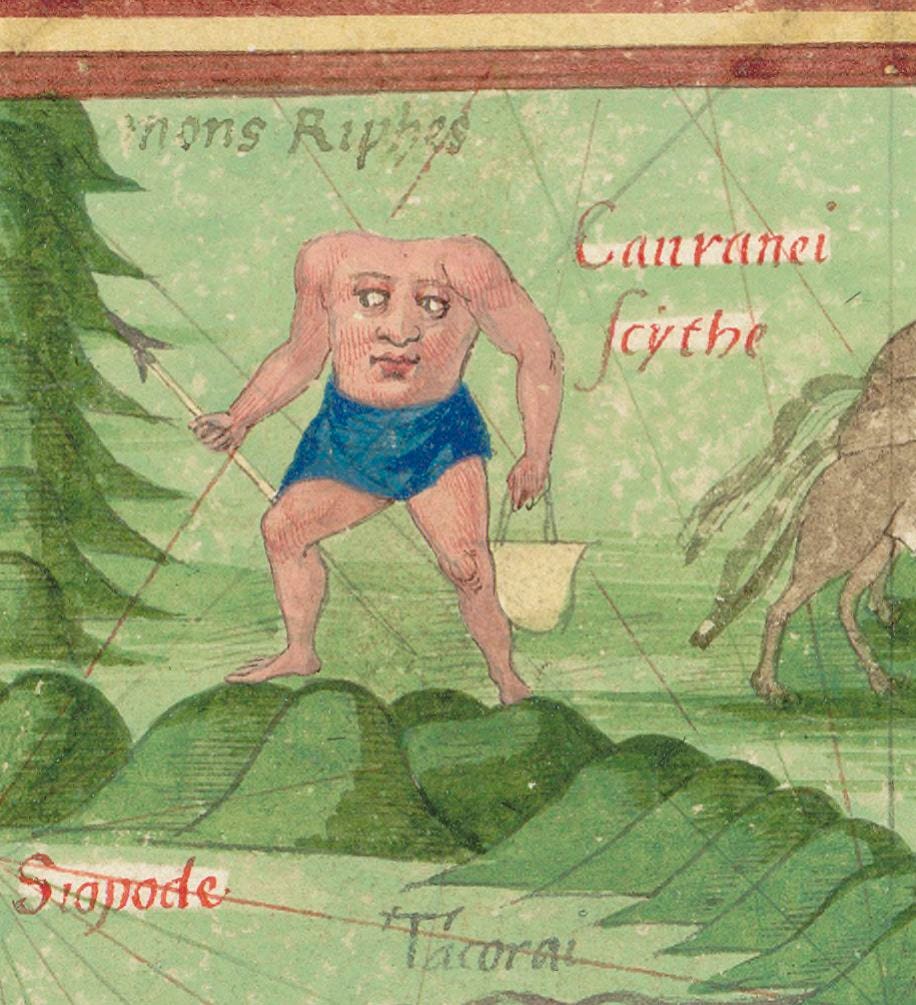

The Qazim was the home of the headless people — whom Niccólo began calling akephaloi for lack of a better word — and they made their dwellings from thick reeds and boughs woven together to float on the placid waters. In this way, the akephaloi lived upon the Qazim and spent much of their time happily swimming between the various floating homes which moved on the gentle eddies. They spent hours in the water each day, speaking and singing to each other, floating in the salty sea, foraging for food in the shallows. And they never needed to come up for air, because their faces were on their backs.

Niccólo thought he was in a dream when the two men first approached him, walking backward with bare torsos and sarongs wrapped around their waists, but no head or neck above their shoulders. Their facial features were triple the size of Niccólo’s and completely located on their backs. Globular eyes peered out from shoulder blades. Curvaceous noses sliced through the air like dolphin fins. Ears protruded like miniature wings. And mouths flapped from the middle of the back, leading directly to the stomach. They were just as confused by Niccólo as he was by them, and initially thought he was some sort of giant monkey — the only other animal they had ever seen that looked like them, but with a bulbous growth above the shoulders. Eventually, through gestures and basic sounds, he managed to convince them he was friendly. They gave him some cloth to cover himself and then they led him up the shoreline to where a small clump of houses floated nearby.

He watched the two men swim out to their home and wished he could join them in their strange abode. The houses were beautiful in an otherworldly way, knotted green domes which seemed to rise from the black waters like natural growths. He could not understand how such creatures were able to survive and thrive, in waterbound houses no less, when they had to do everything backwards. To have your hands and feet point the opposite direction of your face seemed like an insurmountable disability, but it clearly had not hindered them.

Exhausted, he fell asleep on the lakeshore and slept through the night. The next morning the donkey showed no signs of moving, and Niccólo was relieved. Despite his gnawing hunger, he wanted to stay and observe the akephaloi for a little bit longer.

The two men who had first found him were called Bleṃṃyes and Dŏrsi, and once Bleṃṃyes understood that Niccólo was famished and had no way of gathering food for himself, he gestured for Niccólo to follow him to his floating home and then brought out plates of fish and fruits. He carefully sat and then blindly lifted food up to Niccólo’s mouth, which required Niccólo to crane his neck to try to receive it. The whole exercise was messy and embarrassing. This was clearly how the akephaloi treated guests, but Niccólo was unused to being hand fed. Eventually his hunger overcame his sense of decorum and he gently tugged the dish away from Bleṃṃyes and began to feed himself. His host swung around in confusion, then watched in stunned reverie as Niccólo raised hand to mouth to devour the white flesh of the fish and the tangy sweetness of the berries. Bleṃṃyes yelled an exclamation and Dŏrsi came stumbling over to witness Niccólo’s dextrous display. Before long, a small crowd had gathered to watch Niccólo eat, with different akephaloi bringing food from their own homes for him to sample. Shellfish and eels and root vegetables and even a kind of dense flatbread, all were passed to him by trembling hands and there were gasps and mutterings as he placed them between his own teeth.

As his appetite waned Niccólo felt rejuvenated, like his mind was climbing out of bed after a winter’s convalescence. He realised that for the akephaloi, being able to eat alone was not an option. With their faces on their backs and their mouths situated at that midway point which is so difficult to reach, they were only ever fed by each other. Niccólo witnessed this partnered eating several times that afternoon, a smoother operation than what had transpired between him and Bleṃṃyes. They communicated to each other in small noises and course corrections to make sure the food ended up where it needed to go.

After Niccólo had been with them for several days and had picked up a little of their language, he learned that every akephaloi was given a ‘twin’ from birth; not a biological twin (though there was a high proportion of twins and triplets among the akephaloi), but a kind of soulmate of the same sex, to help each other in all sorts of daily tasks made difficult by their biology: eating and cooking and bathing and dressing. Almost everything they did, they did in pairs.

As the days went on and he spent more time among the akephaloi, swimming and eating, he was conscious that they had ceased to look at him with envy or wonder, but instead beheld him with a palpable sense of pity. Like they were disappointed for him. Sad that he missed out on the strange intimacy of needing a friend to help keep you alive.

For those who like fiction, I have a new short story out with The Rialto Books Review, titled ‘The Saxophonist’. It’s a story about loneliness, forgiveness, glandular fever, and saxophones. If you enjoy my writing on Waymarkers, I’m sure you’ll like it.

TRBR is are a fantastic publication that actually pays writers and produces beautiful little chapbooks for each volume, selling at only $7 USD. Please consider buying a copy here and supporting this small press publication.

Here are some photos of Volume 26:

This is awesome